In the context of Clock Domain Crossing (CDC), Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF) quantifies how often a synchronization failure might occur.

A failure here refers to the case where:

- A signal crosses from one clock domain to another.

- The signal becomes metastable in the first-stage flip-flop of a synchronizer.

- The metastability persists for more than one clock cycle, so when the second-stage flip-flop samples it, the signal remains metastable.

This results in an unstable or undefined output being propagated into the receiving clock domain — potentially causing logic failures.

📉 Interpreting MTBF Values

-

Higher MTBF → Better system reliability

(i.e., longer time between potential failures) -

Lower MTBF → Higher failure frequency

(i.e., metastability may occur more often)

Thus, designers aim to maximize MTBF to minimize the risk of metastability affecting system behavior.

⚙️ Factors Affecting MTBF

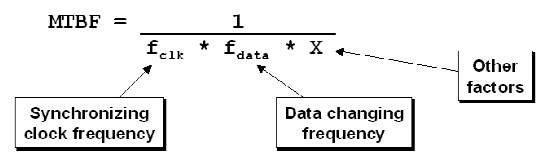

According to Dally and Poulton, the MTBF of a synchronizer circuit depends primarily on:

-

Sample clock frequency (fclk):

- How often signals are sampled into the receiving clock domain.

- Higher sampling frequencies reduce MTBF (failures occur more often).

-

Data change frequency (fdata):

- How frequently the asynchronous input signal changes.

- Faster-changing data increases the probability of violating setup/hold times.

📊 Design Implications

From the above relationships, we can conclude:

- High-speed designs (with fast clocks and frequent data changes) tend to have shorter MTBF, meaning metastability failures may occur more often.

- Designers can improve MTBF by:

- Reducing data transition rates across CDC boundaries,

- Allowing more time for metastability to settle (e.g., adding more synchronizer stages), and

- Using flip-flops with shorter metastability resolution times.